Design with Washington County wildlife in mind: PSU map aims to preserve migration corridors

Published 4:45 am Wednesday, August 6, 2025

From bobcats to butterflies, Washington County’s wild neighbors are getting a little help protecting the scenic route.

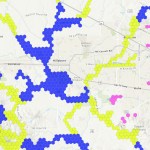

A new statewide wildlife corridor map developed by researchers at Portland State University could help regional city planners and transportation officials better save animals — and drivers — from dangerous road crossings.

The Oregon Wildlife Connectivity Mapping effort, led by the state Department of Fish and Wildlife, identifies key areas where animals are most likely to move across the landscape and where they face the greatest risk from roads and development.

Trending

The map is designed to help state and local governments plan wildlife crossings, preserve habitats and reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions.

A county under development

For growing suburban cities across Washington County — where highways, subdivisions and parks converge — the data could be instrumental.

High-traffic routes like U.S. Highway 26 or Oregon Highway 217 are of particular concern. Collisions between wildlife and vehicles are not uncommon in these areas, especially during migration seasons. The new data allows transportation officials to pinpoint where underpasses, overpasses or fencing might make the biggest difference in saving animal lives.

The research team used habitat modeling and tracking data from 54 species across Oregon, ranging from elk and cougars to salamanders and butterflies. The result is a statewide map of Priority Wildlife Connectivity Areas that highlight where animal movement is most critical.

“We used tracking data where we had it, and presence and absence data to validate where the animals were,” said Martin Lafrenz, a member of PSU’s geography department and the man who led the PSU research team. “In the final map, what you notice about it is that it’s not for a particular species. It’s just animal corridors, generalized. … What the Legislature wanted was just a map of animal corridors in general that they could use to say, OK, you’re going to do this project. It’s going to impact this corridor. So you need to put some kind of a crossing structure or fencing or some sort of mitigation.”

Agency collaboration

Several corridors run through or near the western metropolitan area, including Washington County.

Trending

Because so much of the Willamette Valley ecoregion is privately-owned, according to ODFW, voluntary cooperative approaches are the key to long-term conservation, using tools such as financial incentives, voluntary agreements between ODFW and non-federal landowners and conservation easements.

Collaborating with agencies to uphold and implement current land use regulations is essential for safeguarding farmland, open spaces, recreational areas and natural habitats. This necessitates continuous oversight of shifts in land use across the region, as well as in relevant land use plans and policies.

Washington County’s network of parks and greenways, including the Tualatin Hills Nature Park, Penstemon Prairie and Fanno Creek Trail, already provide important habitat for wildlife. With more planning, those natural areas could be better connected to allow wildlife to safely move between them.

City planners, regional park agencies and state transportation officials may begin using the data later this year as they update transportation and conservation plans.

For Washington County, the PSU research offers a timely roadmap — one that may guide future development toward a safer, more wildlife-friendly future.

How can you help?

The ODFW developed a project specifically for roadkill in Oregon which makes use of data from iNaturalist, an online social network for recording observations of wildlife.

Rachel Wheat, ODFW’s wildlife connectivity coordinator and the overall project lead, highlighted the value of iNaturalist for public participation, stating, “One of the things that we get asked a lot in our public communication is, how can the average person help provide information for connectivity? And one of the best ways that we found to do that is with iNaturalist.”

While the state has some data on large animal road fatalities (like deer and elk) from maintenance crew removals, information on smaller species is limited. This is where iNaturalist proves invaluable.

“Anyone with a cellphone can go out and snap a photo of a roadkill observation that they see. And then we can draw on that information to help identify roadkill hotspots and find the areas where we really need to focus on doing some sort of mitigation, whether that’s crossing structures, habitat modification, or fencing to try to keep wildlife from getting killed on the road,” Wheat said.

— John Baker